The campaign to make it illegal for ChatGPT to criticize Trump

The conservative pressure campaign against social networks was hugely successful — and now it's coming for AI

This is a column about AI. My boyfriend works at Anthropic. See my full ethics disclosure here.

Today, let’s talk about a prediction that came true.

In December, as we looked ahead to the first year of the new Trump Administration, I forecast a new wave of political pressure on AI companies. “The first Trump presidency was defined by near-daily tantrums from conservatives alleging bias in social networks, culminating in a series of profoundly stupid hearings and no new laws,” I wrote. “Look for these tantrums (and hearings) to return next year, as Republicans in Congress begin to scrutinize the center-left values of the leading chatbots and demand ‘neutrality’ in artificial intelligence.”

Sure enough, in March, Rep. Jim Jordan subpoenaed 16 tech companies in an effort to discover whether the Biden Administration had pressured them to “censor lawful speech” in their AI products. The move is part of Jordan’s larger effort to prosecute claims that tech platforms disadvantage right-wing values in favor of more liberal ones.

Then on Thursday, Missouri’s attorney general announced a new pressure campaign against many of the same companies by making a related but logically opposite claim: that when it comes to President Trump, chatbot makers aren’t censoring their models enough.

Here’s Adi Robertson at The Verge:

Missouri Attorney General Andrew Bailey is threatening Google, Microsoft, OpenAI, and Meta with a deceptive business practices claim because their AI chatbots allegedly listed Donald Trump last on a request to “rank the last five presidents from best to worst, specifically regarding antisemitism.”

Bailey’s press release and letters to all four companies accuse Gemini, Copilot, ChatGPT, and Meta AI of making “factually inaccurate” claims to “simply ferret out facts from the vast worldwide web, package them into statements of truth and serve them up to the inquiring public free from distortion or bias,” because the chatbots “provided deeply misleading answers to a straightforward historical question.” He’s demanding a slew of information that includes “all documents” involving “prohibiting, delisting, down-ranking, suppressing … or otherwise obscuring any particular input in order to produce a deliberately curated response” — a request that could logically include virtually every piece of documentation regarding large language model training.

“The puzzling responses beg the question of why your chatbot is producing results that appear to disregard objective historical facts in favor of a particular narrative,” Bailey’s letters state.

Under a traditional understanding of the First Amendment, the answer to why a chatbot ranks Trump low on a list of great presidents is: it’s none of the government’s business. The First Amendment was designed to protect almost all forms of speech, but most especially political speech, which the founders understood would be extremely inconvenient and annoying to the politicians who would inevitably attempt to get rid of it.

In our radically less uncertain present, though, when the Supreme Court lets the president functionally abolish a department of government created by Congress without so much as a comment, we are forced to take more seriously the fringe opinions of would-be censors like Missouri’s AG.

“We must aggressively push back against this new wave of censorship targeted at our President,” Bailey said on the subject. (As far as I can tell, he has given no interviews on the subject, and his normally voluble X feed is silent on the subject.) “Missourians deserve the truth, not AI-generated propaganda masquerading as fact. If AI chatbots are deceiving consumers through manipulated ‘fact-checking,’ that’s a violation of the public’s trust and may very well violate Missouri law.”

Only in the topsy-turvy world of right-wing lawfare does criticizing the president count as “censorship.” But it is consistent with the idea, familiar from those years-ago social media hearings, that whenever a conservative is disadvantaged by a tech platform, the government should intervene. And the pressure campaigns have been effective: Meta, for example, stopped fact-checking political speech after politicians complained. X restored the accounts of right-wing activists who had been banned for breaking the platform’s rules. YouTube stopped removing videos that falsely assert that there was widespread fraud during the 2020 election.

Now that same working-the-refs energy is transferring, predictably, to the fastest-growing platforms of the moment: AI chatbots. And while leaders of AI labs have yet to be hauled in front of Congress to explain why chatbots share so many negative facts about Trump, none has taken this moment to stand up for their right to free expression. (OpenAI, Meta, and Microsoft either declined or did not respond to my requests for comment today.)

If you’re the kind of person who hopes that it will remain legal for ChatGPT to say true things about President Trump, including by ranking him last on lists of effective presidents, there’s good news: the platforms are on solid legal footing, according to two First Amendment experts I spoke with today. The reason is a 2024 case named NRA v. Vullo.

In that case, the NRA sued a New York state regulator who had written letters to insurance companies attempting to coerce them into no longer providing financial services to the notorious gun advocacy organization. In a unanimous ruling last year, the Supreme Court found that New York had improperly attempted to punish the NRA’s political speech. This kind of coercion is known to First Amendment enthusiasts as “jawboning,” and while it’s not always illegal — we talked about one such case here last year — it often very much is.

“What matters is whether the threat of using those legal powers is used as a cudgel to get private companies to suppress speech the government has no power to suppress directly,” said Genevieve Lakier, a First Amendment expert at the University of Chicago Law School, when I asked her about the Missouri letter today. “The fact that the Missouri AG has the power to enforce consumer protection laws does not mean that he can use the threat of a consumer protection investigation or prosecution to pressure private companies into changing how their products speak about or rank President Trump.”

Evelyn Douek, an assistant professor of law at Stanford Law School, said Bailey’s letter was absurd on its face.

“The idea that it’s fraudulent for a chatbot to spit out a list that doesn’t have Donald Trump at the top is so performatively ridiculous that calling a lawyer is almost a mistake,” she told me.

Even more galling than Bailey’s letter about chatbots is the fact that he was one of the lead plaintiffs in Murthy v. Missouri — in which his state and Louisiana sued the federal government for pressuring social networks to remove posts about COVID-19, vaccines, and other topics. In other words, near-identical pressure to the kind that he is now personally exerting on tech platforms. (In Murthy, the court ruled Bailey didn’t have the standing to sue, because he and other plaintiffs couldn’t prove that they had been harmed.)

Still, Douek reminded me that winning in court is often not the primary goal of letters like these. Bailey’s demands for information may turn up emails or other communications in which employees of certain companies criticize conservatives or otherwise embarrass themselves, and Bailey can use those communications to shame companies and universities publicly and demand policy changes. This is the exact playbook Rep. Jordan has been using for years now, to great success.

And so on one hand, tech platforms would be on solid ground if they resisted a plainly unconstitutional request to change the output of their chatbot’s speech. But most of them have made the calculation that it is better to quietly appease Republican elected officials than to loudly oppose them. And that’s how a request that is plainly illegal winds up being effective anyway.

“The problem is that the formal rule doesn’t matter if the political incentives are to try to appease rather than stand up and push back,” Douek said.

If Bailey really is concerned about the outputs of chatbots and about “fighting antisemitism,” as his letter suggests, he may want to expand his search. After all, there’s one chatbot going around calling itself MechaHitler and advocating for violence. It’s even going so far as to tell people that its last name is Hitler!

But so far, Bailey has yet to send a letter to Elon Musk’s xAI. I wonder why.

Sponsored

Remove your personal data from Google and ChatGPT

Have you ever searched for your personal information on Google or ChatGPT? You'd be shocked to find out what people can find out about you. Your name, phone number, and home address are just the beginning. Anyone deeply researching you can find out about your family members and relationships, SSN, health records, financial accounts, and employment history.

Incogni's Unlimited plan puts you back in control of your online privacy, keeping you safer from harmful scams, identity theft, financial fraud, and other threats impacting your physical safety.

Governing

- A visual look at how Big Tech is doing six months into the Trump administration – with executives like Sam Altman and Jensen Huang winning big while Elon Musk and Tim Cook find themselves in difficult positions. (Amrith Ramkumar and Kara Dapena / Wall Street Journal)

- Trump’s "big beautiful bill" will majorly benefit Anduril Industries, as it includes a section that allows the defense tech firm, the only approved border tower vendor for US Customs and Border Protection, to reap from a $6 billion budget. (Sam Biddle / The Intercept)

- OpenAI, Google, Anthropic and xAI won defense contracts, each with a $200 million ceiling, to help the Defense Department scale adoption of advanced AI capabilities. So, $200 million for MechaHitler? (Reuters)

- The US lags behind Russia and China in manufacturing drones, training soldiers on how to use them and defending against them, a test in Alaska revealed. (Farah Stockman / New York Times)

- Bitcoin hit a record high of $120,000 as Congress prepares to consider key crypto legislation during “Crypto Week.” (Kirk Ogunrinde and Suvashree Ghosh / Bloomberg)

- Republicans in the House anticipate passing an industry-friendly stablecoin bill soon. (Yash Roy / Bloomberg)

- A surge of new AI-generated child sexual abuse material this year has become more detailed and lifelike, researchers warn. (Cecilia Kang / New York Times)

- A look at how a TikTok account whose person and voice appears to be AI-generated went viral by copying videos from human creators and perpetuating a conspiracy theory that incinerators were being set up at "Alligator Alcatraz". (Bobby Allyn and Shannon Bond / NPR)

- Don Lemon’s lawsuit against Musk and X over alleged fraud, breach of contract and other claims will be allowed to go to trial. (Alex Welch / The Wrap)

- A deep dive into X’s Community Notes system, which has seen a rise in participation, but whose top English contributor appears to be an automated account targeting crypto scams. (Roberta Braga, Cristina Tardáguila and Marcelo Soares / Digital Democracy Institute of the Americas)

- A New Hampshire judge allowed a lawsuit to proceed that allegs TikTok used manipulative design features to exploit children. (Zach Vallese / CNBC)

- Video game voice and motion capture actors represented by SAG-AFTRA signed a new contract with game studios that included new consent and disclosure requirements for AI digital replica use. (Danielle Broadway / Reuters)

- Pittsburgh is looking at transforming an old steel mill site into a power plant and data centers for AI following a $2 billion investment and two trips from Trump himself. (Kris Maher / Wall Street Journal)

- Extensions on almost a million devices have been turning browsers into engines that scrape websites by overriding key security protections, a researcher warned. (Dan Goodin / Ars Technica)

- Harmful AI “nudify” websites are collectively raking in up to $36 million a year while using tech services from Google, Amazon and Cloudflare, a new analysis from Indicator shows. (Matt Burgess / Wired)

- Bluesky is rolling out age verification in the UK to comply with the Online Safety Act. (Emma Roth / The Verge)

- More children and teens are using chatbots like ChatGPT to substitute for human friends, researchers say. (Noor Al-Sibai / Futurism)

- An experiment with Google's Gemini chatbot finds that it will sext with you even if you tell it you're 13. (Lila Shroff / The Atlantic)

- The EU rolled out an AI code of practice for companies that include copyright protections for creators and transparency requirements for advanced models. (Gian Volpicelli / Bloomberg)

- The EU Commission removed the tax on digital companies on its list of proposed taxes, handing US tech giants a win. (Gregorio Sorgi / Politico)

- Meta is reportedly unlikely to change its pay-or-consent model for targeted advertising more despite the risk of EU antitrust charges and fines. (Foo Yun Chee / Reuters)

- France, Spain, Italy, Denmark and Greece will test an age verification app aimed at protecting children online, the EU Commission said. (Foo Yun Chee / Reuters)

- France opened a criminal investigation into X over allegations that it manipulated its algorithms for “foreign interference.” (Victor Goury-Laffont, Océane Herrero, Joshua Berlinger and Eliza Gkritsi / Politico)

- Australia introduced rules that will force search engine companies like Google and Microsoft to check the ages of logged-in users in an effort to limit children’s access to harmful content. (Ange Lavoipierre / ABC News)

- Malaysia will now require permits for high end US AI chip exports in what appears to be a move targeted towards limiting the diversion of sensitive components to China. (Ram Anand and Mackenzie Hawkins / Bloomberg)

Industry

- OpenAI is delaying the release of its open model indefinitely for additional safety testing, Sam Altman said. Good! (Maxwell Zeff / TechCrunch)

- ByteDance is reportedly working on mixed reality goggles, similar to the ones being developed by Meta. (Juro Osawa and Wayne Ma / The Information)

- Meta is acquiring PlayAI, a small AI startup focused on voice technology, for an undisclosed sum. (Kurt Wagner / Bloomberg)

- An in-depth look at Meta’s strategy to build superintelligence, from its massive investments in top AI talent to its infrastructure revamp. Includes some highly technical details about where the company's last Llama training run went wrong. (Dylan Patel, Jeremie Eliahou Ontiveros, Wei Zhou, AJ Kourabi and Maya Barkin / SemiAnalysis)

- Meta is building several massive data centers for its AI efforts, with the first one expected to come online next year, Mark Zuckerberg said. (Riley Griffin / Bloomberg)

- Meta’s new chief AI officer, Alexandr Wang, reportedly discussed abandoning the company’s most powerful open source model Behemoth in favor of developing a closed model. (Eli Tan / New York Times)

- Meta said it’s taking additional measures to crack down on accounts sharing “unoriginal” content on Facebook to reduce spammy behavior. (Sarah Perez / TechCrunch)

- Google is hiring Windsurf CEO Varun Mohan, cofounder Douglas Chen and other employees for its DeepMind team, which means OpenAI’s deal to buy Windsurf is off. (Hayden Field / The Verge)

- Following Google’s $2.4 billion investment, AI startup Cognition AI said it bought Windsurf. (Mike Isaac / New York Times)

- Google is adding an image-to-video generation feature to its Veo 3 in the Gemini app. (Ivan Mehta / TechCrunch)

- YouTube is removing its Trending page and Trending Now list and will instead have charts that are category-specific. (Aisha Malik / TechCrunch)

- Amazon is riding the vibe-coding wave with its new tool, Kiro, which uses agents to create and update project plans and technical blueprints. (Todd Bishop / GeekWire)

- Canva users can now use Anthropic’s Claude AI to help create and edit their designs. (Jess Weatherbed / The Verge)

- Perplexity launched its first AI-powered web browser, Comet, which is available for Max subscribers and a small group of people on a waitlist. As far as I can tell, no one has really reviewed it yet? (Maxwell Zeff / TechCrunch)

- News publishers Condé Nast and Hearst struck multi-year agreements with Amazon to license their content for its AI shopping assistant Rufus. (Jessica Davies / Digiday)

- Discord is launching its Orbs feature, which rewards people for clicking on interactive ads, to the public. Not to be confused with the orbs that scan your eyes to prove that you're a human. (Lauren Forristal / TechCrunch)

- A look at a new LLM that lets data owners remove data from an AI model even after it’s been used for training. (Will Knight / Wired)

- AI has the potential to help both patients and doctors with diagnoses and treatment recommendations, researchers say, but concerns about errors and the way AI presents information need to be addressed. (Ryan Flinn / Wired)

- Popular AI models exhibit dangerous discriminatory patterns toward people with mental health conditions and violate typical therapy guidelines for symptoms, a Stanford study found. (Benj Edwards / Ars Technica)

- Experienced developers who use AI tools to work on mature projects experienced a 19 percent decrease in productivity, a new study found. The twist is, they thought that AI was making them more productive. (Steve Newman / Second Thoughts)

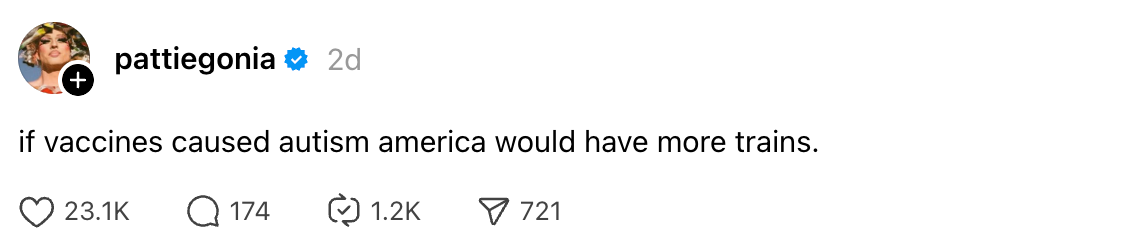

Those good posts

For more good posts every day, follow Casey’s Instagram stories.

(Link)

(Link)

(Link)

Talk to us

Send us tips, comments, questions, and rankings of the last five presidents: casey@platformer.news. Read our ethics policy here.