Who killed Twitter?

Was it Jack Dorsey or Elon Musk? Kurt Wagner and Zoë Schiffer, authors of two new books on the subject, interview each other about what they learned

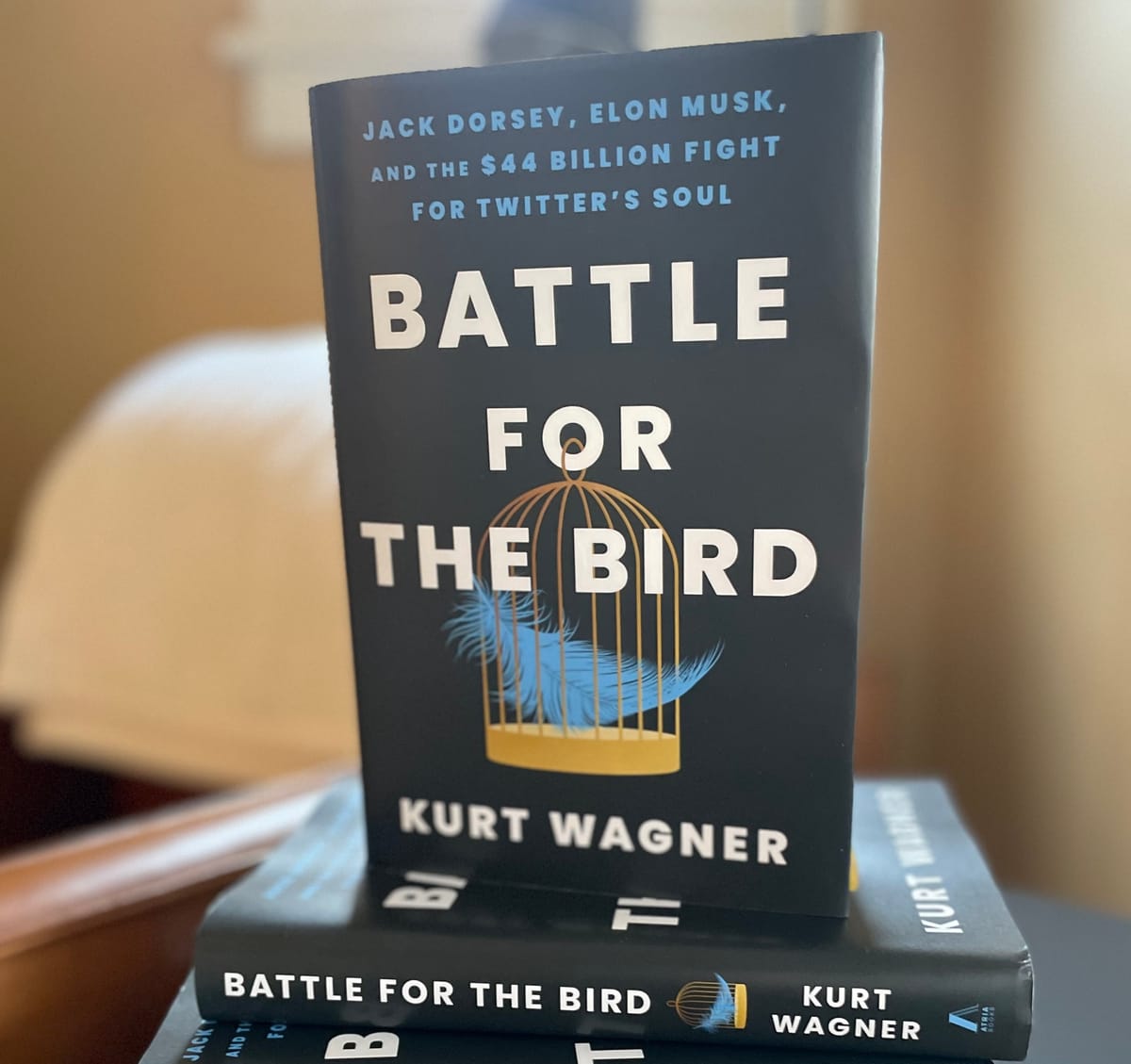

Earlier this week, I published my book, Extremely Hardcore: Inside Elon Musk’s Twitter. Next week, another book on the topic comes out: It’s called Battle for the Bird: Jack Dorsey, Elon Musk, and the $44 Billion Fight for Twitter’s Soul, by Bloomberg’s Kurt Wagner. And it’s excellent.

Today I sat down with Kurt to discuss his book, which he had pitched as a biography on Jack Dorsey but morphed into a deep dive into Twitter’s tumultuous transition into X. Despite not speaking with Dorsey directly, Wagner’s book offers significant insights into the enigmatic leader, from his early years to his 2015 return as CEO and his eventual desperate bid to sell the company to Elon Musk. The portrait isn’t entirely flattering — Dorsey comes across roughly as strange as I suspected — but it is humanizing.

Wagner also paints a vivid picture of Twitter’s culture before Musk, particularly the combination of glamor and goofiness that pervaded the company’s live events. During one all-staff retreat in Houston, Texas, the company brought the supermodel and Twitter power user Chrissy Teigen onstage. She was greeted by a “standing ovation while ‘Hail to the Chief’ played in the background,” Wagner writes. A chyron described her as “mayor of Twitter.” After she sat down, she asked Dorsey if he drinks his own pee.

There really was no other company like it.

Kurt also had some questions for me about the process of writing my book, and the different approaches we take to tackling the same subject matter.

It may seem unusual for competing authors to interview each other about their books on similar topics. But Kurt and I have remained friendly throughout this process, and I have enormous respect for his work. The tale of Twitter is vast and complicated, and I like to think that there’s room for multiple books — particularly ones that embrace different angles and characters, as ours do

[Also I just thought this would be fun to read. And it was! — Casey]

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Zoë Schiffer: When you started writing this book, it was a biography of Jack Dorsey. Did your life fall apart after Musk bought Twitter? Or did it end up feeling like an incredible gift?

Kurt Wagner: It took me a while to appreciate the incredible gift part, although I think at the end of the day, that's exactly what it was. I got very lucky with my timing. I was planning to do a Twitter-Jack book, essentially. And I was literally pitching publishers with a book proposal the week that Elon showed up as the largest shareholder at Twitter. I remember being frustrated in the moment, because a lot of the publishers were asking me, “well, where does Elon fit into this book?” And I kept being like, “He doesn't! This is a Jack-Twitter book! He literally just showed up.”

As the story unfolded, I kept being like, “okay, I'll just add a chapter about that. Okay, I'll add a chapter about that.” And then at a certain point, and I'm embarrassed to say it probably took me all the way until late summer, I finally just was like, “okay, this can't just be a Twitter-Jack book with Elon tacked onto the end.”

Schiffer: How much material did you have to walk away from?

Wagner: A decent amount? I did a lot of condensing. The first chapter of my book now is a Jack Dorsey history chapter. In my proposal, that was maybe three chapters. I originally thought I was going to do a full chapter on Vine, which I didn't end up doing. I thought I was going to do a lot more about Square (now called Block), which I didn't end up doing. But again, I think it was for the best. It kept me more focused than I would have been otherwise, and as we both know, oftentimes when you're forced to condense stuff, it actually makes it stronger.

Wagner: Pivoting a bit: I’ve got a question for you. You wrote your book incredibly fast. You went in knowing what you wanted to write about, I assume, and you did it incredibly quickly. I'm wondering what you learned from that process. If you did it again, would you do it any differently?

Schiffer: So you and I sat down for drinks in March of 2023, and you were already writing your book, and I was feeling really jealous. And we talked really honestly about it. Casey had just told me he didn’t want to write the book, because originally we’d thought about doing it together, but he was focused on Platformer. So if I was going to do it, I needed to do it on my own. And originally I felt like “OK, I’m not going to be able to do it then.” We had that conversation and I was honest with you — I was like, “I don't think it's going to happen.”

But I left that meeting just feeling really bummed that I had spent the last year reporting on this company, feeling like I'd made really good headway on getting in and really, really sourcing up. And then this piece of history was going to be told by a bunch of other people, all of whom are incredible Twitter reporters. But I was like, “I also have a piece of that story that I want to tell.” So I did end up signing the book contract solo and moving forward with it. And when I signed, I think the manuscript was supposed to be turned in April of ‘24. And I went on book leave immediately and was like “if I write 1,500 words a day, I can have the manuscript done by October and I can try to publish it sooner.” I already had done so much reporting, and I knew I was going to focus on the timeframe immediately surrounding the acquisition. I spent the summer working seven days a week, and my husband watched my daughter on the weekends.

I do want to write another book, but I want it to be way less competitive.

Wagner: How did you decide when to end it? I struggled with this. This is a company that has a seemingly endless amount of news and intrigue, right? So how'd you say, “here's where my version of this story stops?”

Schiffer: When Musk named Linda Yaccarino as CEO, at first I thought that was kind of a neat ending. But then it didn't feel like that was actually that big of a change at the company. So by last October, Twitter had become X, it had been a year since the acquisition, and violence broke out in the Middle East. It felt like all of Musk’s product and policy decisions from the last year were culminating in this disinformation disaster on the platform. At that point, I felt like I was able to say, this company is fundamentally different from what it used to be, and the place that it holds in culture and society is not what it once was.

Schiffer: What about for you? Why did you decide to end it where you did?

Wagner: I really wanted to end it before the next phase of the company started. For me, this was a Twitter book. So much of it had been about the history of this prior company and the prior leadership. And so I ended up stopping it at the very end of 2022, with the change of the calendar year. So there was also a natural literal calendar timing that made sense. I had no idea, of course, that he was going to change the name or anything. But I felt by that point, he'd now owned the company for two months, and it didn't feel like Twitter was Twitter anymore.

I ended up putting a bunch of stuff from 2023 into an epilogue. I don't know if that was the right choice, but it feels at least to me, okay, the Twitter version of this story is in the book.

Schiffer: Did you know when you were pitching your book originally that Jack wasn’t going to speak with you?

Wagner: There was a little bit of hesitation at the beginning. Anytime you set out and say, “I want to write a big profile or project,”, and knowing the subject may or may not participate, not having that in the bag…

Schiffer: So at first, you thought there was a chance he might talk?

Wagner: I did. But remember when I started, it had a very different ending. The ending I thought when I first started was, Jack Dorsey leaves his job. That's a very different end than “the company gets sold to Elon and everyone gets fired and everything seems terrible.” So I was optimistic, or at least holding out hope, that maybe if I did enough reporting around Jack that he would ultimately come around.

There's pros and cons to both realities. Of course, I would've welcomed that conversation, but I don't think the book is lacking because of it. And I think in some ways it allows you to delve into areas that maybe you wouldn't have room for if you were trying to squeeze in a bunch of details from an interview with the main subject.

Schiffer: You were able to get Jack's girlfriend from way in the past, and people around him, people who hadn’t spoken about this before, to talk.

Wagner: Yeah, I feel proud of the reporting I was able to do around him. Obviously for me, I do share in the book that I didn't talk to Jack or Elon. I felt like I owed that to the reader, since those are the two main characters in this story. I don't really get into who I did or didn't talk to otherwise. I think savvy readers can probably figure that out if they wanted to. But yeah, I mean, I do feel like part of the appeal was going back and doing a deep dive into history. Sometimes the further away things are, the more likely that people are willing to talk.

Wagner: You had a bunch of Twitter employees that pop up throughout the book and serve as repeat characters. And I'm curious how you decided who to profile.

Schiffer: I come from a labor reporting background. In some ways, I’m not the most natural tech reporter, in that the thing I'm most interested in is the people. I wanted to tell the story of the demise of this important social app, and also the company culture and the people who worked there.

And I specifically wanted to tell it through someone who really didn't like Twitter 1.0, and didn't fit in there, and then was really excited about Elon coming in. And then I wanted to tell the story of someone who stuck it out for different reasons, and maybe wasn't as huge a fan of Elon.

One of my main characters is JP Doherty, the former global director of Twitter Command Center. I knew when I met him that I wanted him to be part of it. He has a really compelling personal story. He had to stay at Twitter because his son, who has health issues and is on his insurance, was having an important surgery in January of ‘23. JP rose up the rinks under Elon despite having serious misgivings about what was going on at the company. And he just seemed like such a standup guy, a really principled person, and someone who wasn't reflexively anti-Elon.

And then Randall Lin, a machine learning engineer, who's kind of my all-in character, he was a lot harder to find. Because it felt like anyone who had really liked Elon, even if they had changed their mind later, probably weren't the biggest fan of my reporting, and didn't want to talk. I really, really, really wanted Esther Crawford to talk to me. And there was not a chance in hell she was going to, although I tried.

Wagner: I was so jealous! I was jealous of a lot of great details in your book, to be clear. But there was a moment a couple of weeks after Elon took over where he emails everyone and he's like, “be in the office this afternoon.” And then he sends a follow-up email: “please fly here if you need to.” And I was joking with sources like, “Hey, could you imagine if someone literally ran to JFK right now and tried to fly to San Francisco because of this email, wouldn't that be hilarious?” And then reading in your book that that's actually what happened — I thought that was really great.

Schiffer: Jack is just such an enigma to me. He just seems really out of touch with reality. I'm curious, given all your reporting, what do you think of him?

Wagner: Yeah, I don't think his leadership style would necessarily be for me, either. He's very hands-off. He's very much a guide, if you will. He doesn't like to make the decisions. He likes to guide people there through questions. And for me, that's not how I would personally prefer to operate. But I do think for all of his flaws as a business leader, he had good intentions. I do think in Silicon Valley there's something to be said about that because not all leaders are doing it for the right reasons, so to speak. And if you want to give Jack some credit, I think he should maybe get some credit there.

He's someone I would actually love to spend time with. From everything I've heard, he's got a really great sense of humor. He's quite witty, a little sharp elbowed, but in a fun way, if he likes you. So I think he would be quite fun to have dinner with.

But I think what ultimately happened was he became blinded by this idea of Elon saving Twitter, and that led him to make what I thought were some very questionable decisions. And when you have built up a community and a culture where people are comfortable being vulnerable, they feel like they're working at a place that's different and unique, and then to see it sort of go through the very typical acquisition playbook where all the decisions are made for the value of shareholders, it just feels like a betrayal.

And I think a lot of employees eventually just felt really betrayed by Jack, even though it wasn't his decision solely. The fact that he wanted this to happen was a real slap in the face to a lot of people.

Wagner: I'm curious actually what you think. I know you didn't focus your book on the Jack Dorsey years, but I'm sure you've talked to several employees who have strong opinions about Jack, and I wonder how much he ever came up in your reporting.

Schiffer: I really strongly feel like there is no Elon buying Twitter without Jack. That situation seems like it was orchestrated by him. He put the wheels in motion.

Employees that I talk to feel like the Jack years were good years for being an employee at Twitter — though they were frustrating years if you wanted to ship a bunch of features and get stuff done. But he encouraged a very open culture, and I think people really appreciated that. People could tag him on Slack and he would go back and forth with people questioning his decisions. And it felt like he really did encourage that type of open dissent, and that created a level of trust at the company, even though he was pretty absent.

In retrospect now, people feel a lot more resentment and frustration. It felt like he brought Elon in, abandoned the company, and then didn't do a lot to stand up for people like [former head of policy and legal] Vijaya Gadde and others who Elon was going after in a pretty horrific way.

Schiffer: How much responsibility do you think Jack feels for what's happened with Twitter now?

Wagner: Well, I don't know for sure. I can only go off of the few things that he said, but I think he feels a little remorse about how things ended up. I don't get the sense he really feels responsible, though. He sort of says, “we had no choice.” The shackles of Wall Street, or the way that the company was set up in terms of a single class of shares versus dual-class shares, he basically says “here are a bunch of things that were outside of my control that were creating this unsustainable environment for Twitter. And we did the best thing we thought possible at the time, which was let it go private and hand it off to Elon.”

I haven't really seen him be like, “this was my mistake.” It's more like “this was the mistake of the environment we were in, and it's a bummer what it's become.”

Schiffer: Yeah, I think that right, although I don't agree with it. If there's someone who had no choice and didn't really have a chance, it's former Twitter CEO Parag Agrawal. You have this great anecdote about how Elon asked Parag to ban the @ElonJet account, and it didn’t happen. And that tips him over into being like, “okay, well, I'm going to have to take the reins.” And I have a different anecdote in my book about how the tipping point was that Elon wanted Parag to fire Vijaya Gadde, and Parag wouldn't do it. Yet I look at those moments and I'm like, even if Parag had done both of those things, do we really think that Elon would've been content to remain just a board member? That seems so far-fetched to me.

Wagner: I agree with you. I think Parag got a really raw deal. I mean, this is someone who worked at Twitter for a decade, presumably gets his dream job getting to run this company he spent a decade working at, and he was essentially handpicked by Jack. So he has the blessing and the encouragement of the founder, and then within three months, before he has any chance to really do anything, Elon shows up and flips the whole thing upside down.

Wagner: One of the things that I think you do a good job chronicling in your book is the mindset of what it's like to work for Elon when you want to work for Elon, right? Grueling hours, working nights, working weekends, literally jumping on a plane at a moment's notice to fly across the country. It's a unique mindset. Not everyone is willing to do that for their employer, certainly not when there's no job security. Why do you think people are willing to do this for Elon?

Schiffer: Elon has kind of a cult of personality around him. He just has such a big reputation in Silicon Valley for doing things that no one else is able to do. For employees, it really feels like, and I think someone says this directly in the book, you can make history if you're there.

He’s a master at framing what he's doing on global, saving humanity-type terms. You're not just buying a social network, you're resurrecting the global town square. You're not just building electric vehicles, you're saving the environment and humanity along with it.

I also think with Elon, it's big risk, big reward. Like with Randall Lin, you see someone who was a mid-level engineer at Twitter 1.0 and then under Elon instantly kind of rises up the ranks because he’s available and in the room and says yes to things and shows a lot of initiative, and Elon likes that. The Tesla engineers are always warning Twitter employees that every day could be their last. But I think there's a little piece of all those people who are like, “well, not me. I certainly won't be one of those people.” And when you're getting put on bigger and bigger projects and Elon's texting you on Signal, I think the feeling of being in his inner orbit feels almost like a drug.

Wagner: It's hard to walk away from the proximity to power.

Schiffer: My final question is, what is your larger takeaway after writing the book? Is there a lesson to be learned in everything that happened?

Wagner: There's this feeling that when tech companies get to a certain size, they lose some influence from the founders or the CEOs. It's sort of like, okay, how much influence can this one individual have on a company that has 8,000 people and has been around for 16 years?

Both Jack and Elon were just so impactful on Twitter in their own ways that it reminded me just how important it is to pay attention to the personalities at the tops of these companies. Knowing that it all trickles down from there, the good and the bad.

Can I throw the same question back to you?

Schiffer: My main takeaway is the internet and the open web as we know it are fragile. And these companies that we take for granted, and we think of as somewhat infallible, are for sale to the highest bidder. And when that happens, which we saw so clearly with Elon, there's very little a board or the employees, and certainly not the users, can do to stop it. With Elon in particular, there are very few checks on his power. I don't know what that means for all of us, but it certainly made me feel like there's a vulnerability to all of this that I hadn't fully appreciated before.

Sponsored

Investors are focused on these metrics.

Startups should take notice.

It takes more than a great idea to make your ambitions real. That’s why Mercury goes beyond banking* to share the knowledge and network startups need to succeed. In this article, they shed light on the key metrics investors have their sights set on right now.

Even in today’s challenging market, investments in early-stage startups are still being made. That’s because VCs and investors haven’t stopped looking for opportunities — they’ve simply shifted what they are searching for. By understanding investors’ key metrics, early-stage startups can laser-focus their next investor pitch to land the funding necessary to take their company to the next stage.

Read the full article to learn how investors think and how you can lean into these numbers today.

*Mercury is a financial technology company, not a bank. Banking services provided by Choice Financial Group and Evolve Bank & Trust®; Members FDIC.

Platformer has been a Mercury customer since 2020.

On the podcast this week: A year after Kevin's fateful encounter with Bing's Sydney chatbot, we check in on the state of artificial intelligence. Then, Perplexity AI CEO Aravind Srinivas joins us to discuss building an "answer engine" that can take on Google — and whether the news business can survive it.

Apple | Spotify | Stitcher | Amazon | Google | YouTube

Governing

- The Kids Online Safety Act now has 60 cosponsors in the Senate, indicating that it could be headed for passage, after several LGBT+ advocacy groups withdrew their objections. But the Electronic Frontier Foundation and ACLU continue to object, and there’s still no companion bill in the house. (Cristiano Lima-Strong / Washington Post)

- X may be violating US sanctions by accepting payments from terrorist organizations and other barred groups for subscriptions, according to a report. Fingers crossed! (Kate Conger / The New York Times)

- Hezbollah was among those terrorist groups, and the report found 28 accounts with checkmarks tied to sanctioned individuals and entities. X later removed them, in a huge victory for its Trust and Safety Center of Excellence. (Jon Brodkin / Ars Technica)

- A federal judge set an October 2026 trial date for the FTC antitrust suit against Amazon. (David Shepardson / Reuters)

- Trump’s Truth Social won approval from the SEC for a merger with Digital World Acquisition, a SPAC, allowing the company to become publicly traded and to access $300 million in investor funds. (Drew Harwell / Washington Post)

- The US Patent and Trademark Office denied OpenAI’s request to trademark “GPT,” saying that the term is “merely descriptive” and unable to be registered. Here’s one problem that Gemini Advanced with Ultra 1.0 will not have! (Devin Coldewey / TechCrunch)

- Congress still isn’t ready to regulate AI ahead of the 2024 elections, despite numerous instances of AI-powered misinformation. (Brian Fung / CNN)

- Meta is reportedly cutting payments to news organizations that fact-check potential misinformation on WhatsApp. (Kalley Huang and Silvia Varnham O’Regan / The Information)

- A company allegedly tracked visits to 600 Planned Parenthood centers across 48 states and shared that data with a large anti-abortion ad campaign, an investigation found. (Alfred Ng / Politico)

- New York City sued TikTok, Meta, Snap and YouTube for negligence, gross negligence, and public nuisance, saying the platforms fueled the nationwide mental health crisis. (Ashley Gold / Axios)

- TikTok says it will increase efforts to combat fake news and covert influence operations ahead of June’s European Union elections. (Foo Yun Chee / Reuters)

- Grieving parents of children killed in school shootings are using AI to generate their children’s voices in automated calls to lawmakers, in a new campaign aimed at promoting gun safety. I truly believe we are going to regret using synthetic voices this way — they can only lower trust in society. (Joanna Stern / The Wall Street Journal)

- Weakening end-to-end encryption risks undermining human rights, the European Court of Human Rights ruled, amid an EU Commission proposal for the creation of backdoors for law enforcement to decrypt messages. Relieved to see this. (Ashley Belanger / Ars Technica)

- Russian, North Korean, Iranian and Chinese-backed groups are using AI tools like ChatGPT to help research their targets and improve cyberattacks, Microsoft and OpenAI say. (Tom Warren / The Verge)

- A Hamas-aligned hacking group targeted Israeli software engineers, attempting to trick them into downloading malware before the Oct. 7 attack, according to Google researchers. (Aggi Cantrill / Bloomberg)

- Some startups are worried that the EU’s antitrust crackdown on Big Tech companies will affect the number of deals and exit routes they have. (Javier Espinoza / Financial Times)

Industry

- Sora, OpenAI’s new text-to-video app, is rolling out to select creators and cybersecurity experts. While it’s all marketing for now, the videos are impressive in a way that made me feel that sensation of AI vertigo all over again. (Steven Levy / WIRED)

- OpenAI is reportedly developing a web search product that will compete with Google. But details are scarce. (Aaron Holmes / The Information)

- A look at OpenAI’s business model that questions whether the company’s fast-growing revenues will be enough to get the company all the way to a superintelligent AI. (Madhumita Murgia and George Hammond / Financial Times)

- Sam Altman reportedly pushed back on the idea that he is seeking trillions of dollars for his chip venture. The figure apparently refers to how much participants would need to invest in real estate, data centers, and chips, among other costs. (Stephanie Palazzalo / The Information)

- Altman is also currently the sole owner of OpenAI Startup Fund, the company’s venture capital fund, according to the filing. This is weird! (Dan Primack / Axios)

- OpenAI founding member and AI researcher Andrej Karpathy has left the company. No word on what he’s doing next; he previously worked at Tesla. (Jon Victor and Amir Efrati / The Information)

- TikTok now has a native app on the Apple Vision Pro. (Jon Porter / The Verge)

- Many people are returning their Apple Vision Pros, saying the experience wasn’t worth the high price tag. But some are waiting for a second version. (Leander Kahney / Cult of Mac)

- Apple is reportedly ramping up its AI efforts, and is near completion on a new tool for Xcode that will rival Microsoft’s Copilot. (Mark Gurman / Bloomberg)

- Google will work with an Environmental Defense Fund unit to track and attribute methane emissions using the company’s AI and mapping technology. (Aaron Clark and Jessica Nix / Bloomberg)

- Google has reportedly launched Goose, an internal AI model that helps employees code faster. (Hugh Langley / Business Insider)

- Developers will now have access to a wider range of Google Gemini models. (Frederic Lardinois / TechCrunch)

- The new Gemini 1.5 model is almost ready for consumers, Google says, and is now available to developers and enterprise users. No disrespect to my dear friend David but I do not understand one word of what Google is doing here. (David Pierce / The Verge)

- YouTube is now letting users integrate music videos into Shorts. The move comes as Universal Music Group’s music remains unavailable on rival TikTok. (Aisha Malik / TechCrunch)

- Meta added two new directors to Meta’s board following Sheryl Sandberg’s departure: Broadcom CEO Hock E. Tan and Arnold Ventures co-founder John Arnold. (Kurt Wagner / Bloomberg)

- Meta will start charging a 30 percent fee on boosted posts for Facebook and Instagram iOS apps, passing along Apple’s fee from the App Store. (Emma Roth / The Verge)

- Bluesky and Mastodon users can’t agree on how to bridge the two social networks, and the way these ecosystems interact could establish the next era of social media. A funny account of how some Mastodon users are reacting in horror to the idea that the two services could interoperate. (Amanda Silberling / TechCrunch)

- Slack is launching a slew of AI tools to help summarize long threads and answer work questions. If your Slack threads are so long you need an AI to summarize them, maybe just delete Slack from your workplace? I think it’s worth a shot! (Emma Roth / The Verge)

- DuckDuckGo added a password-syncing feature to its privacy browser that will keep passwords, bookmarks and favorites across devices without having to set up an account. (Wes Davis / The Verge)

- “Romantic” AI chatbots actually harvest deeply personal information and frequently sell or share data they collect, new research says. (Thomas Germain / Gizmodo)

- AI is challenging a decades-long social contract: the robots.txt file that website owners use to govern web crawlers. (David Pierce / The Verge)

Those good posts

For more good posts every day, follow Casey’s Instagram stories.

(Link)

(Link)

(Link)

Talk to us

Send us tips, comments, questions, and book reviews: casey@platformer.news and zoe@platformer.news.