The case for a little AI regulation

Not every safety rule represents "regulatory capture" — and even challengers are asking the government to intervene

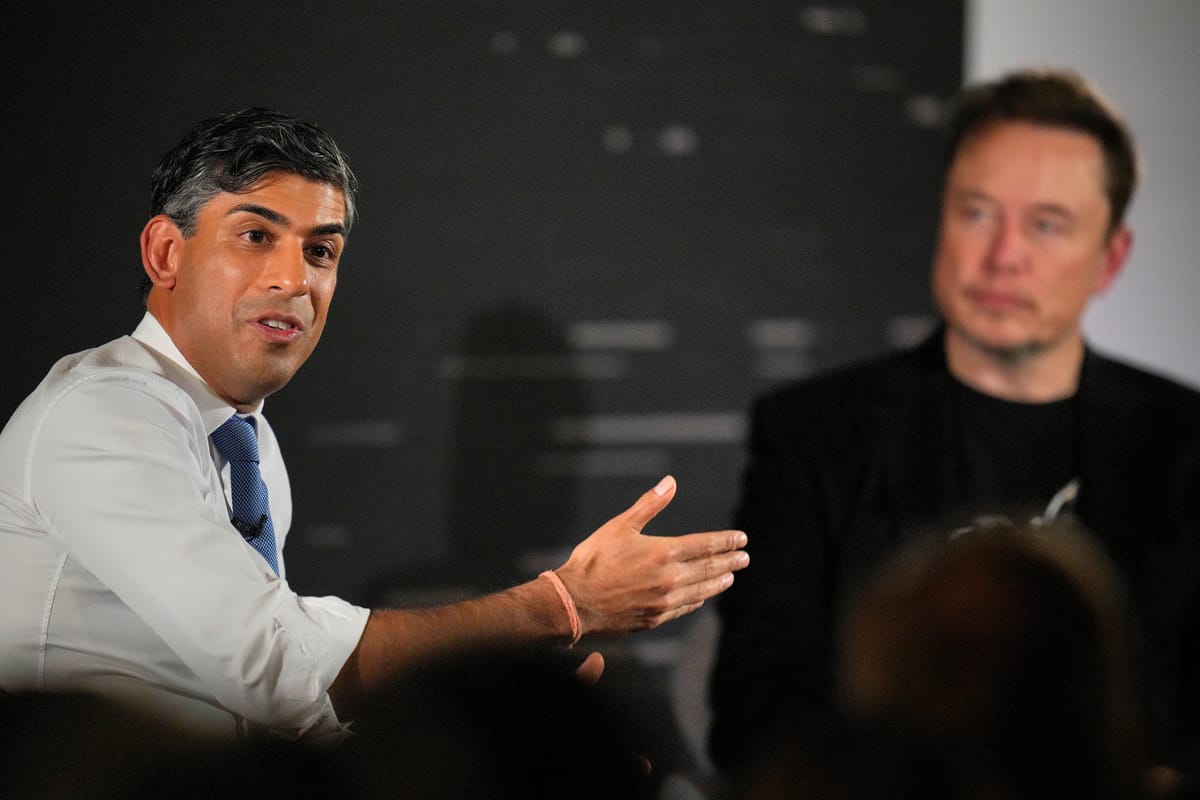

Today, as a summit about the future of artificial intelligence plays out in the United Kingdom, let’s talk about the intense debate about whether it is safer to build open-source AI systems or closed ones — and consider the argument that government attempts to regulate them will benefit only the biggest players in the space.

The AI Safety Summit in England’s Bletchley Park marks the second major government action related to the subject this week, following President Biden’s executive order on Monday. The UK’s minister of technology, Michelle Donelan, released a policy paper signed by 28 countries affirming the potential of AI to do good while calling for heightened scrutiny on next-generation large language models. Among the signatories was the United States, which also announced plans Thursday to establish a new AI safety institute under the Department of Commerce.

Despite fears that the event would devolve into far-out debates over the potential for AI to create existential risks to humanity, Bloomberg reports that attendees in closed-door sessions mostly coalesced around the idea of addressing nearer-term harms.

Here’s Thomas Seal:

Max Tegmark, a professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology who previously called to pause the development of powerful AI systems, said “this debate is starting to melt away.”

“Those who are concerned about existential risks, loss of control, things like that, realize that to do something about it, they have to support those who are warning about immediate harms,” he said, “to get them as allies to start putting safety standards in place.”

A focus on the potential for practical harm characterizes the approach taken by Biden’s executive order, which directs agencies to explore individual risks around weapon development, synthetic media, and algorithmic discrimination, among other harms.

And while UK Prime Minister Rishi Sunak has played up the potential for existential risk in his own remarks, so far he has taken a light-touch, business-friendly approach to regulation, reports the Washington Post. Like the United States, the UK is launching an AI safety institute of its own. “The Institute will carefully test new types of frontier AI before and after they are released to address the potentially harmful capabilities of AI models,” the British Embassy told me in an email, “including exploring all the risks, from social harms like bias and misinformation, to the most unlikely but extreme risk, such as humanity losing control of AI completely.”

Near the summit’s end, most of the major US AI companies — including OpenAI, Google DeepMind, Anthropic, Amazon, Microsoft and Meta — signed a non-binding agreement to let governments test their models for safety risks before releasing them publicly.

Writing about the Biden executive order on Monday, I argued that the industry was so far being regulated gently, and on its own terms.

I soon learned, however, that many people in the industry — along with some of their peers in academia — do not agree.

II.

The criticism of this week’s regulations goes something like this: AI can be used for good or for ill, but at its core it is a neutral, general-purpose technology.

To maximize the good it can do, regulators should work to get frontier technology into more hands. And to address harms, regulators should focus on strengthening defenses in places where AI could enable attacks, whether they be legal, physical, digital.

To use an entirely too glib analogy, imagine that the hammer has just been invented. Critics worry that this will lead to a rash of people smashing each other with hammers, and demand that everyone who wants to buy a hammer first obtain a license from the government. The hammer industry and their allies in universities argue that we are better off letting anyone buy a hammer, while criminalizing assault and using public funds to pay for a police force and prosecutors to monitor hammer abuse. It turns out that distributing hammers more widely leads people to build things more quickly, and that most people do not smash each other with hammers, and the system basically holds.

A core objection to the current state of AI regulation is that it sets an arbitrary limit on the development of next-generation LLMs: in this case, models that are trained with 10 to the 26th power floating point operations, or flops. Critics suggest that had similar arbitrary limits been issued earlier in the history of technology, the world would be impoverished.

Here’s Steven Sinofsky, a longtime Microsoft executive and board partner at Andreessen Horowitz, on the executive order: