How the tech industry soured on employee activism

When social justice protests swept the country in 2020, tech companies mostly welcomed employee activism. The Gaza demonstrations are getting a much different reception

I.

In the early aughts, a dominant cultural philosophy in Silicon Valley, at least from an employer branding perspective, was “bring your whole self to work." Popularized by a 2015 Ted Talk, the sentiment was not intended to be taken literally: your whole self needed to be productive, and professional, and not too radical in its politics. But the idea stands in stark contrast to the one that has replaced it: that only the part of yourself that gets work done should come to the office. Those who bring in anything else may be promptly shown the door.

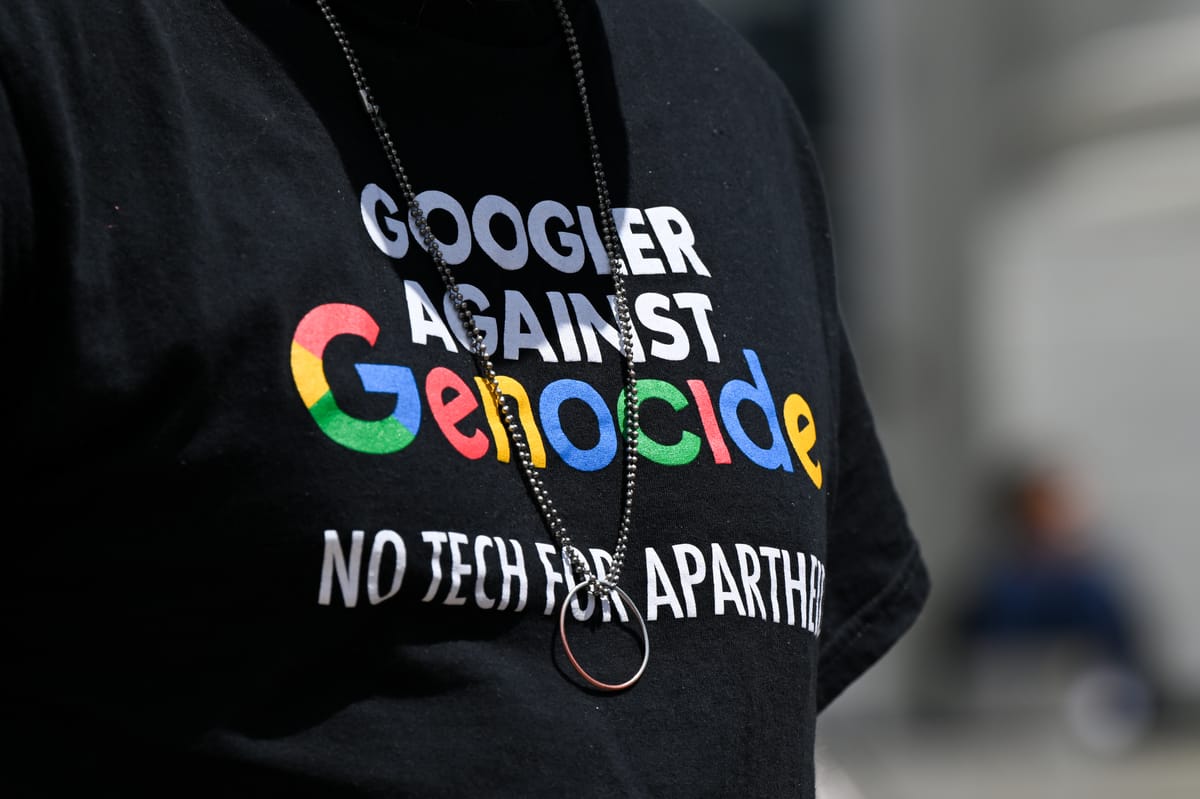

Nowhere has this been more apparent than in the corporate response to employee activism over Israel and Gaza: in the past two months alone, Apple allegedly disciplined retail employees for wearing pro-Palestine paraphernalia, Google fired 50 employees in connection with protests about Israel, and Meta removed Workplace posts from employees voicing support for people in Gaza,

It’s no accident that declining tolerance for employees’ political speech has coincided with the tech industry’s self-described era of efficiency. As companies continue to conduct mass layoffs, and the hiring process remains slow and arduous, employers have more leverage than at any time since the pandemic began.

I’m sympathetic to the idea that employees should engage in activism only during non-work hours. But separating work and life isn’t always easy in a post-pandemic world, where many people work from home and routinely feel each sphere of life bleeding into the other. As the war in Gaza continues to roil workplaces across the country, I find myself doubtful that such a neat separation is possible — and curious about what the downstream impacts will be on both employees and the companies they work for.

“Increasingly, we’re seeing employers have to grapple with a thornier set of issues, because employees are using political activism as a cudgel against management,” says Bruce Barry, a professor at Vanderbilt University’s Owen Graduate School of Management, who specializes in workplace rights. “Just look at Google firing workers and issuing statements about what they do and don't want happening in the workplace. It’s so interesting because not that long ago, Google was a place where they were cultivating open dialogue about anything and everything.”

To help puzzle this out — and to understand what has changed since the George Floyd protests in 2020, when tech companies were likelier to celebrate their employees’ activism — I spoke to employees at Coinbase, Google, Apple, and Amazon, to get their thoughts about the tech industry’s evolving stance on employee speech.

II.

In 2020, Coinbase CEO Brian Armstrong published a memo dictating his company’s new attitude toward workplace activism. “Be company first,” he wrote. He encouraged his staff to put “the company’s goals ahead of any particular team or individual goals.” Later, he added that Coinbase would not focus much on issues outside its core mission. It also wouldn’t engage on broader societal issues or “advocate for any particular causes or candidates internally that are unrelated to our mission.” Armstrong encouraged employees who didn’t align with this approach to take a severance package and leave.

The memo was instantly polarizing inside and outside Coinbase. It came during a moment when protests over police brutality had captivated the country and companies were reckoning with accusations of racism in the workplace. Diversity and inclusion hadn’t yet resulted in meaningful changes for many underrepresented minorities in tech, despite how often it was mentioned on company websites.

“Why stay and put effort into this work if it’s just tokenized into recruiting points and not actually improving the sense of belonging and psychological safety,” wrote a Coinbase employee on Slack, according to messages viewed by the New York Times.

Shortly after, the employee resigned, along with about 60 of her colleagues. At the time, Coinbase had around 600 employees.

The policy makes sense on paper — but it misses what happens when politics become personal. Vanderbilt’s Barry says he likes to show his class the Coinbase policy and ask if they think it’s good. “Students often say ‘yeah!’” he noted. “The point they're missing is, this policy works well until it doesn’t,” he added. “Firms get compelled into certain issues they can't necessarily depoliticize.”

Four years later, I was curious how the company has changed since Armstrong published his memo.The company has continued to track employee engagement through an annual survey, and says that employees generally report being happier than they were in 2020.

“The survey results indicate a steady rise in our collective sense of belonging since adopting our mission-driven strategy,” L.J. Brock, the company's chief people officer, wrote in an email to Platformer. “In our latest survey, 86 percent of employees expressed a strong sense of belonging. Additionally, those who feel a strong sense of belonging are twice as likely to remain with Coinbase and four times more engaged overall.”

I asked a Coinbase spokesperson if the company’s workplace racial diversity had declined since the memo came out.